- Home

- Nick Carter

Checkmate in Rio Page 12

Checkmate in Rio Read online

Page 12

Nick attached a short, cryptic note to the clippings and addressed the envelope containing them to Milbank's New York lawyers, knowing that Hawk would be apprised of the contents as soon as Axe's New York branch received them. Then, activating Oscar Johnson, he sent off a radio message — also ostensibly to his lawyers — which said:

URGENTLY REQUEST CHECK BACKGROUND HISTORY CARIOCA CLUB OWNERS IMPORTERS LUIZ SILVEIRO AND PEREZ CABRAL. AM CONSIDERING CLOSING BUSINESS DEAL PENDING YOUR INFORMATION AND SUBSEQUENT TO DISCUSSION R AND SELF WITH CABRAL THIS EVENING. ESPECIALLY IMPORTANT INVESTIGATE CABRAL SINCE HAVE REASON TO BE SURE OF SILVEIRO. HAVE ALREADY INSPECTED CLUB AND FIND IT GOING CONCERN WITH AFFILIATIONS OLD FRIENDS OF OURS. URGE SWIFT ACTION CUT RED TAPE IF NO FURTHER WORD SOONEST.

The answer came back: EXPECT DEFINITIVE REPORT TWENTY-FOUR HOURS. FOLLOWUP READY IF REQUIRED.

Twenty-four hours! He certainly demanded swift action, that old dynamo in Washington. It meant that whatever Nick might be doing twenty-four hours from now, he'd have to drop it and get on the radio to Hawk or someone else would be on the way to take over… perhaps to look for the pieces of Nick Carter and Rosalind Adler as well.

At least they'd know where to start looking.

Almost five o'clock.

He drove downtown and left his registered letter at the Post Office, then sat down at a sidewalk café to sample an agua de côco con ouiski and wonder if he should not take this opportunity to make some sort of check on Appelbaum and de Freitas. He decided that it would be far better to follow the Cabral-Carioca Club lead before doing any outside digging, and that he preferred his ouiski with ordinary agua or preferably soda.

Nick looked at his watch and grinned suddenly. There was something he wanted to do before the stores closed. Hawk would be furious, but naturally a man like Robert Milbank could be expected to buy a few souvenirs for his lady friend or friends… Aquamarine, now, or amethyst, or golden topaz. Any of these would go well with Rosalind. He paid for his drink and went off on a shopping tour.

* * *

"I didn't even see her," she said tonelessly. "I didn't even say goodbye."

Luisa Continho Cabral sat with her hands folded on her lap, her eyes fixed on the richly carpeted floor.

"I don't quite understand," said Rosalind gently. "You mean that you weren't here when your mother… when your mother died?"

"No, I wasn't home. And neither was she."

Congealed misery stared out of the nineteen-year-old eyes, the small, piquant face was drawn and pale. But her small bones were finely formed and the dark, sad eyes were enormous and curtained with long, soft lashes; her thick jet-black hair curled about her tiny ears. If she looks at all like her mother, Rosalind thought, Maria must have been very beautiful. She had seen her picture in Washington, but it had had the lifeless quality of a passport photo and conveyed little of the essential woman. If this kid could ever smile with happiness, she would be radiantly beautiful.

"I understand that you've been studying in Lisbon," said Roz, feeling it was time for a minor change of tack.

"Studying!" The girl laughed bitterly. "As if I could study when I knew something was wrong and no one ever wrote to me! He said she was away from home! He said that, but mother never wrote to tell me. How could I know where she was?"

"There are always times in people's lives," Rosalind ventured, feeling her way carefully, "when they find it difficult to sit down and write a letter. Perhaps it was because she was ill, and didn't want you to worry. I take it that she used to write you frequently?"

There was a brief pause.

"No," Luisa said reluctantly. "Neither of us wrote very often. I know she was busy with many things, and at school you…" she shrugged hopelessly. "We used to make a joke about the annual letter. But it was as if there was no need to write; we knew how much we thought about each other. Especially since my father…" Her words trailed off. Rosalind saw tears gleaming on her lashes.

"Perhaps we've talked enough about it for the time being," Rosalind said quietly. "I was really hoping that we might be able to…"

"Why do we talk about it at all?" the younger girl burst out suddenly. "Why did he send you here? Was it to question me? Does he want to know what I think? I'll tell him what I think, if that is what he wants! There is no need for you!"

"I'm sure there is no need for me at all." Rosalind made her voice calm and dispassionate, but little lights were beginning to flash inside her mind. "But I wonder why you think he sent me here to question you? He asked me to come, yes. But why in the world would he pick a perfect stranger, and not even supply me with the questions to ask? And I can assure you that he didn't."

Luisa looked her full in the face.

"Then why did he ask you?" And the small mouth stopped its trembling.

"I have no more idea than you have," Rosalind said coolly. She waited for a moment, noting the reaction of guarded curiosity, and added off-handedly: "He did say that he felt you were too much on your own."

Luisa almost spat. "He said that! Since when has he ever given a… a…" She tried to say damn, but her convent training held her back. "He has never cared before," she finished lamely.

"I'm not sure that he does now," said Rosalind, hoping that it was not too bold a stroke.

Luisa stared. "Just — exactly — who — are — you?" she asked, in a small, baffled voice.

"Just someone who would like to have met your mother," Rosalind said quietly, pulling on her gloves. "And who didn't — I must confess — take much of a shine to your stepfather. Of course you don't need to mention that to him unless you want to."

"I never talk to him anymore," Luisa said distinctly.

I hope you're being honest, little girl, thought Rosalind, or the chances are I may just fall right on my face. But at least Nick knows where I am. Just as he did yesterday when I was at the museum, she thought in flash of resentment.

"Then perhaps you will not mention to him that I had a message for your mother from someone in the States, someone who wanted very much to know why your mother was no longer writing to them, either."

Luisa looked at her. "Someone in the United States? I did not know my mother knew anyone there. But then I did not know she knew anyone in Salvador."

"In Salvador?" It was Rosalind's turn to stare. "Why Salvador?"

"Because that is where my stepfather Cabral said that my mother died."

"Oh," said Rosalind, and ran completely out of conversation. She fumbled with her bag and gloves. "You mean that…? I'm sorry, Luisa, dear. I've pounced on you like the Thing from Outer Space, and I can see that it was wrong of me. It's the sort of intrusion I would have resented very much myself. But perhaps you won't mind too much if I call you within the next few days and…?"

"Who was it?" Luisa asked crisply. "Who was it in the States who wanted to know about my mother?"

Rosalind felt an almost overwhelming surge of pity as she looked at the small, lovely figure of Maria Cabral's only child.

"An old man," she said gently. "Someone she had known for many years, and who was worried about her. He wanted something from her — a message, a picture, a Christmas greeting — anything. But now I'll have to… now I'll have to take the message." She was rising as she spoke. "From what he told me, I know I've missed meeting someone very wonderful. But I know that he'll be glad that I met you. By the way, I wonder if I might use the telephone? A friend of mine was going to pick me up here…"

"Don't go," Luisa said suddenly. "Please. I want to talk to you. I want to hear about the old man." She put her hand on Rosalind's arm. "Something's wrong here. Something's very wrong. I have to talk to someone. Even if you tell my stepfather. I have to talk to you."

"Let's talk, then," Rosalind said gently, "if you're sure that's what you want. But surely you must have friends that you can talk to?"

Luisa made a small sound of disgust.

"They are children, all of them, who go nowhere without a chaperone. My friends, they are in Lisbon. And the few people I

know here — pah! they have lived such sheltered lives. I think that you are different."

Rosalind grinned suddenly, unaware that her face lit up like a happy street urchin's.

"A sheltered life I have not led," she said, and laughed out loud. "That's the last thing in the world anyone could ever accuse me of. Someday I must tell you about the one chaperone I had — poor old gibbering thing… But that'll keep. Isn't there some place a little… uh… a little less like an auditorium, where we can talk?"

The Cabral living room was an immensity of rich carpeting and tapestry, much too vast for any pretense of intimacy.

"There is my mother's sitting room," Luisa said hesitantly. "I think I would like you to see that."

"I should like that, too," said Rosalind.

* * *

Nick climbed into the Jaguar laden with packages. There was an alligator bag for Rosalind and a couple of striking shirts for himself; a topaz ring for Rosalind, and a butterfly-wing pipe tray for Hawk, who would hate it; an unset amethyst for Rosalind, and an old-fashioned tourmaline brooch for someone else in New York; some filmy underwear for Rosalind, and a wild beach hat for himself; an aquamarine choker for Rosalind, and a spray of flowers for Luisa Cabral. Luisa Continho Cabral, he corrected himself, wondering how she felt about her stepfather. Wondering how he himself felt about Luisa's stepfather.

Not quite six o'clock. It wouldn't hurt to be a little early.

Which was why he was parked half a block away from the Cabral homestead shortly after six and watching Perez Cabral enter by a side door, having approached on foot with a caution that seemed somewhat unnecessary for someone going into his own home after a long, hard day of interviewing inquisitive police officers.

* * *

"I was at school," Luisa said, "and with Christmas coming, I did write. But he wrote back and said that mother was not well, and because she was not well she was going to Salvador to stay with relatives of his. I did not even know, before that, that he had relatives in Salvador. He also said that she would not be away for very long, so I could write here and he would forward my letters. But she never answered. Then he wrote to say that I should not come home for Christmas, because nobody would be here. At last I could not stand it any longer, and I wrote to say that I was coming home. And when I got home…" her voice broke. "When I got home there was no one but the old housekeeper. She said that my stepfather had flown to Salvador to my mother's funeral. He did not want me to be there, because — because someone had been driving my mother in an automobile and there had been a dreadful accident. A dreadful accident." Her voice broke completely.

Rosalind was silent. There must be something to say, something right, but she did not know what it could be. So she asked what she wanted to know.

"When did she go to Salvador? As far as you know, that is."

"Early in December."

"And when did you come home?"

"Last week! It was just last week! If I had only come home sooner…!"

"It would not have made the slightest bit of difference," Rosalind said gently. "Nothing, nothing, would be changed. Except that you yourself would have had so much more misery."

"I don't believe that," Luisa said with sudden intensity. "I know my mother would have written to me that she was ill if she'd had the slightest chance. If she was well enough to go riding around in an automobile, she was well enough to write to me. She must have known he'd write and tell me that she'd gone away. Mustn't she? Surely she would have written before she went away?"

"Perhaps she did," said Rosalind carefully. "But it's possible that, in the flurry of going away, she forgot to mail the letter. Have you looked to see if there might be any note for you in her desk drawer, or anywhere else?"

"I've looked through everything," Luisa said slowly. "Not for a note, but just for something… anything. But she's all gone."

"Is there a picture of her anywhere? A favorite book, perhaps? Something that was really close to her?"

"I don't know; I don't think so," Luisa said indifferently. "I suppose you'd like something for that old man in the States?"

Rosalind nodded. "If possible. Something that you can spare, yourself. But I do think you may have missed a message from her."

Luisa looked at her intently. "Why do you think that?"

"Because I know that your mother was a very remarkable woman," Rosalind said ambiguously.

"All right," Luisa said thoughtfully. "Let's look again."

She started pulling open the desk drawers.

"It doesn't seem right for me to go into your mother's personal things," said Rosalind, itching to get her practiced hands into the drawers.

"Nothing seems right," said Luisa. "You might as well."

"If you really want me to," Rosalind said, feigning reluctance.

There was absolutely nothing to indicate that Maria Cabral had been anything other than a civic-minded wife and mother with a number of social responsibilities.

But there was a message — an imprint, on the blotter — of something Maria Cabral had been writing… when? Perhaps when someone had stopped her from writing anymore, because the message was brief and incomplete. Or perhaps its incompleteness was due to nothing more than the way she had placed her writing paper on the blotter.

"Pierce, I must see you," Rosalind could just manage to decipher. "It is… indiscretion… no way out of it. Silveiro… watching… since he saw me… heart is sick… discovery… husband Perez… Club as a front for…" And that was all.

"What is it?" Luisa was staring at her. "What are you looking at like that? There is nothing there but the blotter — I see."

She did.

" 'Heart is sick… discovery… husband Perez…' " Luisa murmured, incredulous. " 'Club as a front for…' For what?" She turned her puzzled gaze on Rosalind. "And why should Silveiro be watching her? She found out something about Perez, that's it! Something terrible!" Luisa clutched at Rosalind's arm and squeezed so hard that it hurt. "Something so terrible that he killed her! That's what happened — he killed her! He killed her! He killed her!" Her voice was a passionate scream of rage and hatred and the lovely eyes were wild with growing hysteria.

"Luisa! Stop that at once!" Rosalind's voice was low but crisply commanding. "You can't jump to conclusions like that. And even if you do, you don't have to scream them all over the house. Use your head. What it he did?"

Luisa subsided suddenly. For one fleeting moment she seemed to be thinking it over. Then an expression of absolute terror stamped itself across her face.

"That's right, Luisa. What if he did?" The voice was smooth as velvet, friendly as the rustle of a rattlesnake's tail. Rosalind turned slowly, feeling her heart miss a beat.

Perez Cabral stood at the open door his face a twisted mask, his pale eyes shooting splinters of ice.

The Wayward Widower

"So, Luisa. Miss Montez. While the cat is away the mice are scampering through the house and into the drawers, is that it? And coming up with a murderer! How very clever of them. And how very foolish."

His menacing eyes raked over them, lighted on the desk, and came back to bore into Rosalind. Luisa shrank against her.

"And you, Senhorina Montez. Is this the reason you accepted my invitation with such alacrity? To meddle and search, to worm things out of my daughter?"

"Your daughter!" Luisa cried, stung into reply. "You are not my father! You are a hateful, horrible…"

"Hush, Luisa," Rosalind said calmly. "It is scarcely prying, Senhor Cabral, for a girl to open a drawer in her own mother's room. And if you object to my presence here, you should not have asked me. What did you think we were going to do — sit and stare at each other in silence?"

"Hardly that, dear lady." Cabral's voice was almost a purr. "But I would not have expected you to go so far as to read something strange and sinister into a few innocent dents on the blotting paper. Nor would I expect you to encourage the poor child in this sudden wild idea about me… killing my wife!"

Luisa made a little moaning sound. "My mother," she whispered.

"Mr. Cabral, I think this has gone far enough," Rosalind said levelly. "Oh, I'll admit that the 'wild idea' flashed across my mind for a moment. But for all your talk of wanting to help Luisa, I don't think you've been fair to her. Why didn't you tell her exactly what happened? Why couldn't you have at least let her go to the funeral with you? Can't you see that it's only natural to wonder why you didn't? If there's anything 'strange and sinister' about this, you can easily set things straight by being a little more open with Luisa."

"And with you, I suppose, Miss Montez?" Cabral smiled thinly. "No, I think it is you who owe the explanation. I must congratulate you on your righteous indignation, but I am afraid I am not completely convinced of your good intentions. Sit down, both of you. I will listen. And you, Miss Montez, will do the talking. Sit down, I said!" His cold eyes sparked angrily.

"I'll do nothing of the sort," said Rosalind firmly. "There is absolutely no excuse for your rudeness and your insults. And if you expected to do business with Robert, you can forget about it. I'm leaving." She heard Luisa catch her breath beside her. "Luisa, I'm sorry about all this. Perhaps you'd like to come out with me for a while, until — until the temperature cools down a little."

"Oh, yes, please!" Luisa whispered fervently.

"Oh, no," said Perez Cabral. "I am very sorry, but I cannot let you leave." He was smiling, but the velvety voice had turned to sandpaper. "Least of all while you think so badly of me, and certainly not with Luisa."

"Please let us by," said Rosalind coolly. "Come, Luisa." Then she stopped. Cabral barred the door with his body, holding an automatic in his hand.

"You will not leave this room," Cabral said slowly and distinctly. "Either of you. Until you, Miss Montez, tell me why you have chosen to meddle in my life. And do not worry about your friend. I will take care of him." The twisted smile became an ugly grimace. "He is not due here for several minutes. I will meet him outside and say regretfully that you left early, since Luisa was in no mood for company. I will, of course, have locked you in. And then I will come back, and you will talk."

Checkmate in Rio

Checkmate in Rio The Death Dealer

The Death Dealer Safari for Spies

Safari for Spies Berlin

Berlin The Death’s Head Conspiracy

The Death’s Head Conspiracy The Istanbul Decision

The Istanbul Decision The Liquidator

The Liquidator The Black Death

The Black Death The Weapon of Night

The Weapon of Night The Berlin Target

The Berlin Target Temple of Fear

Temple of Fear Earthfire North

Earthfire North Beirut Incident

Beirut Incident White Death

White Death Night of the Warheads

Night of the Warheads Double Identity

Double Identity The Spanish Connection

The Spanish Connection Rhodesia

Rhodesia Death of the Falcon

Death of the Falcon The Executioners

The Executioners Run, Spy, Run

Run, Spy, Run Circle of Scorpions

Circle of Scorpions Agent Counter-Agent

Agent Counter-Agent The Living Death

The Living Death War From The Clouds

War From The Clouds Assassin: Code Name Vulture

Assassin: Code Name Vulture The Death Strain

The Death Strain The Aztec Avenger

The Aztec Avenger Six Bloody Summer Days

Six Bloody Summer Days Operation Petrograd

Operation Petrograd Operation Che Guevara

Operation Che Guevara The Omega Terror

The Omega Terror The Terrible Ones

The Terrible Ones Assassination Brigade

Assassination Brigade Assault on England

Assault on England The Judas Spy

The Judas Spy A Korean Tiger

A Korean Tiger Operation Moon Rocket

Operation Moon Rocket Butcher of Belgrade

Butcher of Belgrade Law of the Lion

Law of the Lion Peking & The Tulip Affair

Peking & The Tulip Affair Death Island

Death Island The Jerusalem File

The Jerusalem File The Defector

The Defector The Fanatics of Al Asad

The Fanatics of Al Asad Dragon Flame

Dragon Flame Eighth Card Stud

Eighth Card Stud Operation Snake

Operation Snake The Mark of Cosa Nostra

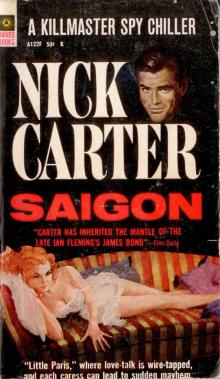

The Mark of Cosa Nostra Saigon

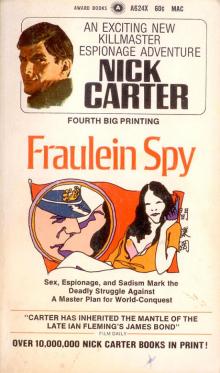

Saigon Fraulein Spy

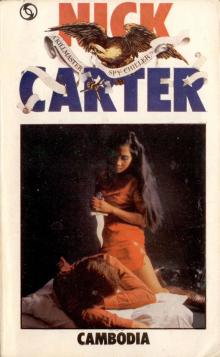

Fraulein Spy Cambodia

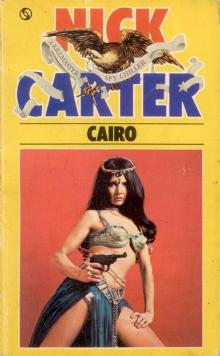

Cambodia Cairo

Cairo