- Home

- Nick Carter

Assassin: Code Name Vulture

Assassin: Code Name Vulture Read online

Annotation

He was a highly paid professional, killing anyone, anywhere, for a price. A murderer who relished his work, lovingly watching each victim writhe in blood.

The Intelligence establishment named him The Vulture — "the scarlet vulture," his mechanized talons dripping with human blood. Destroying The Vulture was Nick Carter's next assignment.

But before Carter could get to his lethal quarry, he had to hunt down another man. A bizarre double of The Vulture, forced into becoming the assassin's perfect weapon — and his next agonized victim!

* * *

Nick Carter

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

* * *

Nick Carter

Assassin: Code Name Vulture

Dedicated to The Men of the Secret Services of the United States of America

One

I licked my parched lips with a thick tongue and squinted up at the sun overhead. There was a taste of old paper in my mouth and a dull but insistent buzzing in my ears.

There was no way of knowing exactly how long I had lain unconscious at the side of the small, scraggly thornbush. When I first came around, I couldn't remember where I was or how I had gotten there. Then I saw the twisted, gleaming hulk of the wreckage, the small Mooney aircraft that had fallen like a wounded hawk from the cloudless sky. The half-crushed strips of metal — remains of the violent crash — rose just thirty yards away above the brown grass of the veldt, and thin wisps of smoke still wafted skyward from it. I recalled now how I had been hurled from the plane as it hit the ground and then crawled away from the raging flames. I figured from the position of the sun that several hours had passed since the mid-morning crash.

Stiffly, and with much pain, I propped myself into a sitting position feeling the hot, white clay against my thighs through my torn khaki trousers. The bush shirt I wore was stuck to my back, and the stink of my own body filled my nostrils. Holding a hand up to shade my eyes from the sun's glare, I looked out over the tall lion grass that seemed to extend endlessly in all directions, broken only by the occasional greenery of a lonely umbrella acacia. There was no sign of civilization, nothing but the vast sea of grass and trees.

A vulture moved silently overhead, wheeling and pirouetting. Casting its shadow on the ground before me, the bird hung there obtrusively, watching. The buzzing in my ears became more distinct now, and it occurred to me that it was not in my head after all. The sound came from the vicinity of the accident. It was the sound of flies.

I focused on the wreckage. Then the vulture and swarm of flies reminded me that Alexis Salomos had been with me on that plane — he had been piloting it when the trouble came. I squinted my eyes but couldn't see him anywhere near the wreck.

Rising weakly I found that my legs were rigid. My entire body ached, but there didn't seem to be any broken bones. A long cut on my left forearm was already healing, the blood caked dry. I regarded the smoldering wreckage darkly. I had to find Alexis to see if he had survived.

The buzzing of the flies became louder as I approached the plane's carcass. I leaned down and peered into the cockpit, but I couldn't spot my friend. My stomach felt queasy. Then as I was walking around the front of the wreck, past a charred propeller and a crumpled piece of fuselage, I suddenly stopped.

Alexis' body lay in a grotesque, bloody heap about ten yards away. He had been thrown clear, too, but not before the plane had mashed him. The front of his head and face were caved in from impact with the windshield of the plane, and it looked as though his neck had been broken. His clothing had been ripped to shreds, and he was covered with caked-dry blood. Large brown flies covered his body crawling into all the crimson crevices. I started to turn away, a little nauseated, when I saw movement in the long grass behind the corpse. A spotted hyena was inching up, aware of my presence but too hungry to care. While its appearance was still registering in my brain, the hyena closed the small distance between itself and the body and grabbed at the exposed flesh of Alexis Salomos' side, savaging a piece off.

"Get away, damn you!" I shouted at the beast. I picked up a stick of burnt wood and flung it at the hyena. The animal loped away through the grass carrying the chunk in its bloody jaws. In a moment it was gone.

I stared down again at the twisted body. I didn't even have a shovel to bury it with so I had to leave it to be destroyed by scavengers within twenty-four hours.

Well, there was nothing I could do. Alexis Salomos was just as dead with or without a burial. They had finally caught up with him and killed him, and they had almost gotten me, too. At least until this moment I had somehow survived. But the biggest test of my luck might just lie ahead, for I figured I was about halfway between Salisbury and Bulawayo, in the deepest part of the Rhodesian bush country.

I walked around the wreckage until it hid the corpse again. Just before the sabotaged Mooney had begun sputtering and coughing up there at five thousand feet, Salomos had mentioned that we would be passing over a tiny village soon. From what he had said, I calculated that the village was still fifty to seventy-five miles to the southwest. With no water or weapons my chances of getting there were very slim. The Luger and the sheath knife that I generally carried had been left at my hotel in Salisbury. Neither of them could be concealed beneath my bush shirt and, anyway, I had not foreseen the need for them on this particular plane ride to Bulawayo. I was on leave from my regular duties with AXE — America's super-secret intelligence agency — and had merely been accompanying an old friend from Athens whom I had met, quite by accident, in Salisbury. Now that friend was dead, and the wild story he had told me had become credible.

I walked to a nearby termite mound, a heap of hard white clay as high as my head with many chimneys that served as entrances. I leaned heavily against it, stared out toward a distant line of fever trees, and tried to ignore the buzzing of the flies on the other side of the wreck. It was just three days ago that I had met Alexis Salomos at a small restaurant near the Pioneer Memorial Park in Salisbury. I was sitting on the terrace looking down on the city when Salomos was suddenly standing beside my table.

"Nick? Nick Carter?" he said, a slow smile starting on his handsome, swarthy face. He was a square-jawed, curly-haired man in his forties whose eyes looked steadily at you with a bright intensity, as if he could see secrets inside your head. He was a newspaper editor in Athens.

"Alexis," I said, rising to extend my hand. He took it with both hands and shook it vigorously, the smile broadening to match my own. "What the hell are you doing in Africa?"

The smile faded, and I realized for the first time that he looked different from the way I had remembered him. He had helped me ferret out a KGB man who had stolen documents important to the West a few years ago in Athens. He seemed to have aged considerably since then. His face had lost its healthy look, particularly around the eyes.

"Do you mind if I join you?" he asked.

"I'll be offended if you don't," I answered. "Please sit down. Waiter!" A white-aproned young man came to the table, and we both ordered a British ale. We made small talk until the drinks came and the waiter left, then Salomos fell pensive.

"Are you all right, Alexis?" I finally asked.

He smiled at me, but the smile was thin and taut. "I have had trouble, Nick."

"Anything I can do?"

He shrugged his square shoulders. "I doubt if there is anything anybody can do." He spoke good English but with a marked accent. He took a long swig of the ale.

"You want to tell me about

it?" I asked. "Or is it too personal?"

He gave a bitter laugh. "Oh, it is personal, my friend. You might say it is extremely personal." His eyes met mine. "Someone is trying to kill me."

I watched his face. "Are you sure?"

A wry smile. "How sure must I be? In Athens a rifle shot breaks a window and misses my head by inches. So I take the hint. I take a vacation to see my cousin here in Salisbury. He is an import merchant who emigrated here ten years ago. I thought I would be safe here for awhile. Then, two days ago a black Mercedes almost struck me on the main boulevard. The driver, who drove up onto the curb, looked exactly like a man I had seen before in Athens."

"Do you know who the man is?"

"No," Salomos said, shaking his head slowly. "I had seen him coming from the Apollo Building recently when I was doing a little snooping there." He paused and stared at his ale. "Have you ever heard of the Apollo Lines?"

"An oil tanker company, isn't it?"

"That is correct, my friend. The biggest tanker line in the world which is owned by my countryman, Nikkor Minourkos."

"Oh, yes. I know of Minourkos. A billionaire ex-sailor. A recluse; nobody ever sees him these days."

"Correct again," Salomos said. "Minourkos withdrew from public life almost ten years ago while still a relatively young man. He is believed to spend almost all his time in his penthouse in the Apollo Building near Constitution Plaza where he conducts his business. Personal contacts are made primarily by associates close to Minourkos. Almost no one ever obtains a personal audience with him."

"Very rich men seem to place a high value on their privacy," I said, sipping the ale. "But what does Minourkos have to do with the attempts on your life?"

Salomos took in a deep breath and let it out slowly. "About six months ago, Monourkos' behavior began to change. This was of particular interest to me, and other newspaper editors, of course, because any information about Minourkos is exciting and important to the readers of the Athens Olympiad. So I began taking notice when Minourkos, who has always stayed out of politics, began issuing public statements against the ruling junta in Athens. Suddenly he announced that the leaders among the colonels were weak and socialistic. He claimed they betrayed the 'revolution' of April 21, 1967, and implied that Greece would be better off with the restoration of Constantine II or some other monarchy. He referred to the danger of leftists like Papandreou and suggested that there needs to be another 'shake-up' in Greek government."

"Well," I said, "the man has a right to grow a sudden interest in politics after all these years. Maybe he's bored with trying to spend his money."

"It seems to be going farther than that. A man like Minourkos can buy a lot of friends. Generals and colonels are seen going to and from his penthouse, but they won't talk about the visits to the press. And there are rumors of a private army being financed by Minourkos at a specially built camp in northern Greece and at one on Mykonos, an Aegean island.

"Lastly, there is the recent disappearance of Colonel Demetrius Rasion. A Minourkos-dominated newspaper concludes he drowned while boating at Piraeus, but his body was never found. Nikkor Minourkos is now starting a big campaign to have Rasion replaced with a man of his own choosing, a fascist named Despo Adelfia. The junta does not want Adelfia, but its new and genteel leaders are afraid of Minourkos and his friends on the staff of generals."

"An interesting situation," I acknowledged, "But do you think Minourkos is embarking on a terror campaign with ideas of a bloody coup?"

"Perhaps. But there are other possibilities. There are new faces that none of us newsmen have seen before coming and going from the penthouse atop the Apollo Building; Minourkos himself still stays in hiding. I did notice, however, that one of the new faces belongs to a Greek-American named Adrian Stavros."

My eyes narrowed slightly on Salomos. "Stavros in Athens?" I murmured slowly. "Keeping company with Minourkos?"

"It appears so. Unless…"

"Unless what?"

"Well. Since Minourkos' recent utterances have been so out of character, perhaps he himself has not been the source of them."

"A Stavros takeover of the Minourkos empire?"

"Perhaps against Minourkos' will," Salomos suggested. "Perhaps there has already been a small coup, a hidden one. Since Minourkos is so secretive and always deals through subordinates, it would be possible to kill or capture him and operate under his name, and spend his vast sums of money without anyone taking notice for a time. It was just after I implied such a theory in my editorial that the first attempt was made on my life in Athens."

The haunted look had returned to his eyes. I remembered the AXE file on Adrian Stavros and realized that he was capable of just such a maneuver. Stavros had spent his college years demonstrating with placards at Yale. Then he had become involved in a radical bombing of a CIA office, and later he had made an attempt on a senator's life. He had escaped the clutches of the FBI and the CIA and had buried himself somewhere in Brazil where he had graduated to big-time crime like smuggling and assassination. Since the evidence against him in the States has been slim, the US had not tried to get him back. But they kept a watch over him in Brazil.

"And the man who tried to run you down here in Salisbury?" I asked. "You had seen him coming from the penthouse at the Apollo Building?"

"Yes, Nick," Salomos said. He swigged the rest of his ale and looked over the hibiscus-lined balustrade down the hill to the city. "I am getting desperate. A friend of my cousin who lives in the country outside Bulawayo has asked me to visit him for a short time until this blows over. I have accepted his invitation. A rented plane waits for me at the airport. I will fly it, since I am a licensed pilot, and will enjoy the trip. That is, if I can forget about…" There was a brief silence, then he looked over at me. "Nick, I would be very grateful if you could accompany me to Bulawayo."

I knew that Alexis Salomos would not ask if he were not desperate with fear. And I still had several days leave left before I received another assignment from David Hawk, the enigmatic director of AXE.

"I've always wanted to see Bulawayo," I said.

A look of relief came over Alexis' face. "Thanks, Nick."

Two mornings later we were airborne. Salomos was a competent pilot, and it appeared that the flight across the wild country of Rhodesia would be uneventful and pleasant. Salomos flew low so that we might spot occasional game animals and interesting topographical features of the bush. The flight seemed to raise Salomos' spirits, and he seemed very much like his old self. But at mid-morning, just about halfway to Bulawayo, the serenity of the morning was transformed into a nightmare.

The small Mooney aircraft, a two-seater, began coughing. Salomos was not concerned at first, but then it became worse. He throttled the small engine, but that only made matters more difficult. We lost altitude and started into a wide, banking spin.

Salomos swore in Greek, then his face went pale. He studied the panel and glanced over at me. "The fuel gauge reads full," he shouted over the sputtering engine. "It has not moved from its original position this morning." He banged on the glass that covered the gauge, but nothing happened. The needle stayed fixed on the letter F.

"We're out of gas," I said incredulously. That was bad news in any airplane, particularly in a small one.

"Not quite, but we're running out fast," Salomos said, pulling the Mooney into a temporary, steep glide and fighting the controls. "This plane was sabotaged, Nick. The gauge was frozen in position, but the tanks were almost empty when we started out. It had to have been on purpose."

"Jesus," I muttered. "Will you be able to land it?"

"There is no airfield anywhere near here," he said, straining to keep the plane from going into a tailspin. "But we will have to try a landing on the open veldt — if I can keep it in a glide pattern."

"Anything I can do?"

"Yes. Pray." Alexis glanced at me. "I am very sorry, Nick."

"Never mind that," I said. "Just get this thing down." I didn't even ask abou

t chutes. There was no time. We were headed in a steep glide toward the grassy veldt.

The engine coughed and sputtered once more, then stalled for good as we saw the ground rush up at us. I figured it was over. There seemed to be no reasonable expectation of living through it.

Five hundred feet We swooped downward like a bird with a broken wing. Three hundred. The acacia trees slid past underneath. One hundred. Salomos' face was rigid with tension, and his arms were corded with his efforts at the controls. Then there was a rushing of grass and thornbush at a dizzying speed, a wing being rent by the limb of a twisted tree, and the plane nosing up slightly at the last moment, sliding around sideways. The impact threw us against the front of the plane. There was a grinding and screeching of metal and a loud shattering of glass, and our bodies were punched around in the small cabin. Then came the final crashing stop, with my door flying open and my body flying head over heels through the grass to a crunching impact with the hard ground.

I remember nothing beyond that, except for. crawling painfully through the grass, instinctively dragging myself away from the plane, and then the explosion with the sound of flames crackling somewhere behind me.

Two

I tried to push the memory of the crash out of my mind as I leaned heavily against the hard clay of the tall termite mound. But it was more difficult to eliminate the expression on the face of Alexis Salomos, the way it had looked in Salisbury, when I had said I would fly to Bulawayo with him.

There was still the insistent buzzing of flies beyond the glinting metallic hulk of the wrecked plane, but I tried not to listen. I focused again on the distant line of fever trees on the grassy horizon. Somewhere I had learned that fever trees sometimes announce the presence of water. But these trees were not in the direction that I had to walk to reach the village.

In a way I felt responsible for Salomos' tragic death. He had trusted me to help, and I had been incapable of doing so when he had needed me. He had expected counsel from me, and I had not foreseen the danger of the small plane. Also, I felt guilty because I had not totally believed his incredible story. However, his bloody corpse was blatant proof that at least part of his theory had been valid. Someone had wanted him dead. Whether that person was someone living in the penthouse above the Apollo offices in Athens was still open to question.

Checkmate in Rio

Checkmate in Rio The Death Dealer

The Death Dealer Safari for Spies

Safari for Spies Berlin

Berlin The Death’s Head Conspiracy

The Death’s Head Conspiracy The Istanbul Decision

The Istanbul Decision The Liquidator

The Liquidator The Black Death

The Black Death The Weapon of Night

The Weapon of Night The Berlin Target

The Berlin Target Temple of Fear

Temple of Fear Earthfire North

Earthfire North Beirut Incident

Beirut Incident White Death

White Death Night of the Warheads

Night of the Warheads Double Identity

Double Identity The Spanish Connection

The Spanish Connection Rhodesia

Rhodesia Death of the Falcon

Death of the Falcon The Executioners

The Executioners Run, Spy, Run

Run, Spy, Run Circle of Scorpions

Circle of Scorpions Agent Counter-Agent

Agent Counter-Agent The Living Death

The Living Death War From The Clouds

War From The Clouds Assassin: Code Name Vulture

Assassin: Code Name Vulture The Death Strain

The Death Strain The Aztec Avenger

The Aztec Avenger Six Bloody Summer Days

Six Bloody Summer Days Operation Petrograd

Operation Petrograd Operation Che Guevara

Operation Che Guevara The Omega Terror

The Omega Terror The Terrible Ones

The Terrible Ones Assassination Brigade

Assassination Brigade Assault on England

Assault on England The Judas Spy

The Judas Spy A Korean Tiger

A Korean Tiger Operation Moon Rocket

Operation Moon Rocket Butcher of Belgrade

Butcher of Belgrade Law of the Lion

Law of the Lion Peking & The Tulip Affair

Peking & The Tulip Affair Death Island

Death Island The Jerusalem File

The Jerusalem File The Defector

The Defector The Fanatics of Al Asad

The Fanatics of Al Asad Dragon Flame

Dragon Flame Eighth Card Stud

Eighth Card Stud Operation Snake

Operation Snake The Mark of Cosa Nostra

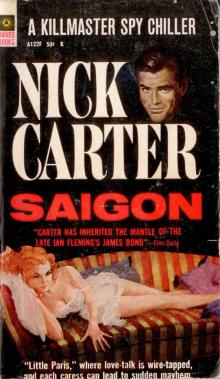

The Mark of Cosa Nostra Saigon

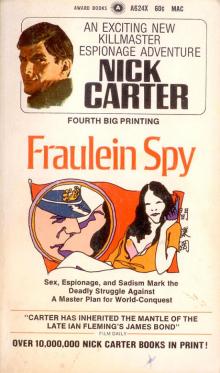

Saigon Fraulein Spy

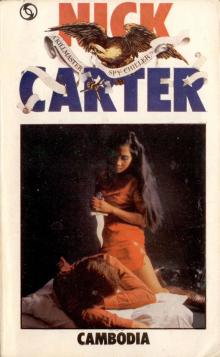

Fraulein Spy Cambodia

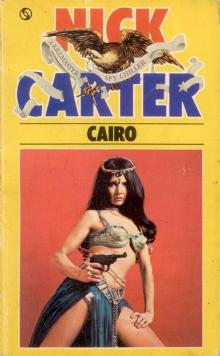

Cambodia Cairo

Cairo