- Home

- Nick Carter

The Jerusalem File Page 11

The Jerusalem File Read online

Page 11

The rest of the story was pure luck. The rest of the story is always luck. Luck is how most people stay alive. Brains, muscles, guns, and guts only add up to fifty percent. The rest is luck. Luck was that no one frisked me past the gun, that Qaffir liked to see a guy tie himself up, and that the next move was tying my hands to my ankles. When Qaffir left the room to get Mansour arrested, I grabbed the knife, cut myself loose, hung in there (or up there) as though I were tied, and when Qaffir came back, I jumped him, lassoed him, beat him, and killed him. And the beating, I add, was just to make the body-swap look legitimate.

After I locked up Ali Mansour, I went to the door and called for "the woman." I kept one hand close to my face, and all I had to yell was, "Imraa!" Woman]

When they brought her in, I was back at the mirror. I was even smiling. I was thinking of the write-ups in the medical journals. I'd discovered the world's only cure for acne. Death.

The guards left. I turned around. I looked at Leila and she looked at me and her eyes changed from chunks of ice to rivers, and after that, she was in my arms and the veil fell away and the walls came down, and the lady didn't kiss like a virgin.

She stopped just long enough to look in my eyes. "I thought — I mean, they were talking out there — about Qaffir — about — about what he does…"

I nodded. "He does… But he only got as far as my back. Speaking of which…" I loosened her grip.

She stood back, suddenly playing Clara Barton. "Let me see."

I shook my head. "Uh uh. Seeing is not what it needs. What it needs is Novocaine and Aureomycin and probably stitches and a very good bandage. But seeing is something it does not need. Come on. We've still got work to do."

She looked around. "How do we get out?"

"That's the work we've got to do. Think of a way to get out and then do it."

She said, "There are Jeeps parked out in the front."

"Then all we have to do is get to the Jeeps. Meaning all I have to do is pass for Colonel Qaffir in front of his whole damned platoon. How many guys are out there in the lobby?"

"Maybe ten. Fifteen at most" She tilted her head. "You look like Qaffir?"

"Only a little around the mustache." I explained about Qaffir's distinguishing marks. "He was more in bloom than a park in the spring. And that's not the kind of thing that anyone misses. It just takes one guy to say I'm not Qaffir and they'll figure out fast that Qaffir is dead. And then, my chickadee, so are we."

Leila stopped and thought for a minute. "Unless there is no one looking at you."

"I could always wear a sign that says Do Not Look."

"Or I could wear a sign that says Look At Me."

I looked at her and frowned. In the little silence I heard the music. The music coming from down the hall.

"Leila — are you thinking what I think you're thinking?"

"What do you think I think?"

I ran my hand lightly down her robe-covered body. "How will you do it?"

"I worry about how. You just listen for the proper moment. Then you go out and get in the Jeep. Drive around to the back of the hotel."

I looked doubtful.

She said, "You underrate me. Remember, these men hardly ever see women. They see only walking bundles of cloth."

I suddenly looked even more doubtful. I told her I didn't underrate her at all, but I thought she was underrating those guys if she thought she could do her shimmy-and-shake and just walk away like nothing had happened.

She smiled. "Nothing has happened yet." And then she was suddenly out the door.

I started to rifle the colonel's desk. I found his papers and put them in my pocket. I'd already taken his gun and his holster, my knife was strapped into place up my sleeve and I'd rescued Wilhelmina and slipped her into my boot. I also still had my Hertz map with its coffee stains, jam stains, X's, O's, and the circle I'd drawn to match Robey's trip.

I looked at the map. The tiny Syrian town of Rhamaz fell twenty miles within the circle. I started to grin. With all the odds that were going against me, I just might have turned up the billion dollar maybe. The Al Shaitan camp. The Devil's workshop.

The sound effects in the lobby had changed. The music was louder, but that wasn't all. Sighs, mumbles, whistles, murmurs, the sound of seventy whizzing eyes. Leila was strutting her stuff, all right, doing her El Jazzar belly dance. I waited until the sounds reached a crescendo; then I opened the colonel's door and made my way through the crowded lobby as unseen as a fat girl on a Malibu beach.

The Jeeps in front had been left untended and I drove one around to the back and waited, parked behind a clump of sheltering palms.

Five minutes.

Nothing.

Her plan wasn't working.

I'd have to go in there and rescue Leila.

Five minutes more.

And then she appeared. Running toward me. Dressed in her silver spangled costume.

She jumped in the Jeep. "Go!" she said.

I pulled away and we took off. Fast.

A half mile later she began to explain. "I kept going out through the doors to the garden and coming back in with less and less clothes."

I started to laugh. "And they thought when you went out the final time…?"

She gave me a mischievous look and laughed, tossed her head and let the wind blow her hair all around. I forced my eyeballs back to the road and gunned the Jeep as fast as it would go.

Leila Kaloud. Freudian goldmine. Playing around the edges of sex and never getting close to the real thing. Teasing herself as much as everyone else. I said, "Okay, but cover up now. We don't want a thousand eyes on this Jeep."

She struggled into the sack-like robes and wrapped the veil around her face. "So where do we go now?" She seemed slightly miffed.

"A place called Rhamaz. Southeast of here."

She grabbed the map from the seat beside me. She scanned it and said, "We stop at Ilfidri."

I said, "We do not."

She said, "You are bleeding. I know of a doctor who lives at Ilfidri. It's on the way."

"Can you trust the guy?"

She nodded. "Oh yes."

Ilfidri was a small but dense village of low, squat stone houses. A population of maybe two hundred. We got there at twilight. No one was out on the unpaved streets, but the sound of the Jeep was a major event. Curious faces peered out of windows and over stone walls and out of alleys.

"There," Leila said. "The home of Dr. Nasr." I pulled up in front of a white stone box. "I go first alone and say why we're here."

"I think I'll go with you."

She shrugged. "All right."

Dr. Daoud Nasr answered the knock. A short thin man, wrinkled and robed. He took in my Syrian colonel's get-up and a quick alertness brightened his eyes.

"Salaam, my Colonel." He bowed slightly.

Leila cleared her throat and threw back her veil. "And no salaams for your Leila then?"

"Ah!" Nasr threw his arms around her. Then he pulled back and put a finger to his lips. "Guests are inside. Say nothing more. Colonel?" He gave me an appraising look. "I think perhaps you come to my office?"

Nasr put his arm around my back, his robe covering my bloodstained jacket. He led us into a small room. A worn rug covered the concrete floor where two men sat on embroidered pillows. Two others perched on a pillow-covered bench that was built all around the stone wall. Kerosene lanterns lit the room.

"My friends," he announced, "I present you with my good friend, Colonel…" he paused, but only an instant, "Khaddourah." He reeled off the names of the other guests. Safadi, Nusafa, Thuweini, Khatib. All of them middle-aged, shrewd-eyed men. But none of them looked at me with the alarm that Nasr had eyed me with at the door.

He told them we had some "private business" and, with his arm still draped around me, led me off to a room in the back. Leila disappeared into the kitchen. Unintroduced. Unnoticed.

The room was a crude doctor's office. A single cabinet held his supplies. The room had a sink with no

running water and a kind of makeshift examining table; a wooden block with a lumpy mattress. I stripped off my jacket and the bloodsoaked shirt. He sucked in his breath through closed teeth. "Qaffir," he said, and went to work.

He used a spongeful of stinging liquid and took some stitches without anesthetic. I moaned quietly. My back couldn't tell the good guys from the bad. As far as the ends of my nerves were concerned, Nasr and Qaffir were both villains.

He finished his work by smearing some goo on a strip of gauze and winding it around my middle as though he were wrapping a mummy. He stepped back a little and admired his work. "And now," he said, "if I were you, I think I would try to get very drunk. The best help for pain I can give you is aspirin."

"I'll take it," I said. "I'll take it."

He gave me the pills and a bottle of wine. He left the room for a few minutes and came back and threw me a clean shirt. "I ask no questions to a friend of Leila and better you ask no questions to me." He was sponging some liquid onto my jacket and the bloodstains were starting to disappear. "Medically, I advise you to stay here. Drink. Sleep. Allow me to change your dressings in the morning." He glanced up quickly from his dry-cleaning chores. "Politically, you help me much if you stay. Politically, I play a rather complicated game." He said it in French: Un jeu compliqué. "Your presence at my table will help me much… in front of the others."

"The others, I take it, are on the other side."

"The others," he said, "are the other side."

If I read that correctly, my new friend Nasr was a double agent. I raised an eyebrow. "Un jeu d'addresse, go." A game of skill.

He nodded. "You stay?"

I nodded. "HI stay."

* * *

The dinner was a feast. We sat on the floor on embroidered pillows and ate off a cloth that was placed on the rug. Bowls of bean soup, grilled chickens, huge platters of steaming rice. The talk was political. Straight-line stuff. Driving Israel into the sea. Reclaiming all of the Golan Heights. Taking back Gaza and the West Bank to make a home for the poor Palestinians.

I don't dispute the Palestinians are poor and I don't dispute that they've gotten the shaft. What amuses me is the Arab piety, considering their major contributions to the general Palestinian fix. Consider: Gaza and the West Bank were originally reserved for Palestinian States. But Jordan stole the West Bank in '48 and Egypt swallowed the Gaza Strip, and they threw the Palestinians into refugee camps. The Arabs did that, not the Israelis. And the Arabs are the ones who won't let them out.

The Arabs don't even pay for the camps. The food, housing, education, medicine, all that it takes to keep the refugees alive, all of that comes from U.N. money. The U.S. gives $25 million a year and most of the rest comes from Europe and Japan. The Arab nations, with all their talk and their oil billions, kick in a total of two million bucks. And Russia and China, those great champions of the benighted masses, contribute exactly nothing at all.

The Arab idea of helping Palestinians is buying them a gun and pointing it at Israel.

But I said, "Here, here!" And, "Yes!" And, "To victory," and toasted the army and President Assad.

And then I made a toast to Al Shaitan.

Nobody knew much about Al Shaitan. The group I was with was As Saiqa. The Syrian branch of the P.L.O. As Saiqa is the Syrian word for "Lightning." The guys around the table were no bolts of fire. They talked a lot, but they weren't fighters. Planners, maybe. Strategists. Bombasts. I wondered what the Syrian word was for thunder.

The man named Safadi — small, precise mustache, skin the color of a brown paper bag — said he was sure that Al Shaitan was a part of Jebreel's General Command, the Lebanese raiders who hit the Israelis at Qiryat Shemona.

Nusafa frowned and shook his head. "Ach! I beg to differ, mon ami. This is much too subtle for Jebreel's mind. I believe this has the mark of Hawatmeh." He turned to me for confirmation. Hawatmeh heads another fedayeen group, The Popular Democratic Front.

I smiled an I-know-but-I-can't-tell smile. I lit a cigarette. "I'm curious, gentlemen. If the money were yours, how would you spend it?"

There were murmurs and smiles around the table. Nasr's wife came in with a pot of coffee. A chador — something like a full-length shawl — was draped on her head, and she clutched it tightly around her face. She poured the coffee, her presence ignored. She might have been a servant or a shrouded robot.

Thuweini leaned back, toying with his salt-and-pepper beard. He nodded and narrowed his line-ringed eyes. "I think," he said, in a high nasal voice, "I think that the money would best be spent to build a uranium diffusion plant."

No doubt about it, these guys were planners.

"Yes, I think that is very good, no?" He turned to his colleagues. "Such a plant could be built for a billion dollars, and it would be a most useful thing to have."

A do-it-yourself nuclear kit.

"Oh, but my dear and respected friend," Safadi pursed his little mouth, "that is a very long-range plan. And where would we get the technical assistance? The Russians will help our government, yes, but the fedayeen — no — at least not directly."

"And where would we get the uranium, my friend?" The fourth man, Khatib, had added his voice. He held up his cup, while Nasr's woman filled it with coffee and then retreated back to the kitchen. "No, no, no," Khatib was saying. "We need a more immediate plan. If the money were mine, I'd use it to set up fedayeen cadres in every major city in the world. Any country that doesn't help us — we blow up their buildings, kidnap their leaders. That is the only way to justice." He turned to his host. "Or don't you agree, my conservative friend?"

Khatib was watching Nasr with amusement. And under the amusement, his eyes spelled trouble. This is why Nasr wanted me around. His 'conservatism' was under suspicion.

Nasr slowly put down his cup. He looked tired, and more than that, weary. "My dear Khatib. Conservative is not another word for disloyal. I believe now as I have always believed that we turn into our own worst enemies when we try to terrorize the whole globe. We need the help of the rest of the world. We can only earn fear and enmity with terror." He turned to me. "But I believe my friend the colonel is tired. He has just returned from the fighting at the front."

"Say no more." Thuweini stood up. The others followed. "We respect your efforts, Colonel Khaddourah. Our little business here is our own contribution." He bowed. "May Allah be with you. Salaam."

We exchanged salaams and Wa-aleikum as-salaams, and the four polite, middle-aged terrorists retreated into the dusty night.

Nasr led me to the only bedroom. A large, thick mattress on a stone slab, covered with pillows and very clean sheets. He'd accept no protests. His house was mine. His bed was mine. He and his wife would sleep under the stars. It was warm out tonight, after all, no? No, he would hear of no other plan. He would be insulted. And people would talk if they knew he didn't give the colonel his house.

"Leila?" I said.

Nasr shrugged. "She sleeps on the floor in the other room." He raised a hand. "No. Don't give me your Western nonsense. She has not been beaten today, and she will not have to fight tomorrow. You think you get rest with that back on the floor?"

I let him convince me. Besides, it had a trace of poetic Justice. In Jerusalem, she'd told me to sleep on the floor. I shook my head slowly, and thought how impractical virginity is.

* * *

I must have been asleep for half an hour. I heard a sound at the bedroom door. I grabbed my gun. Maybe Nasr had set me up. ("Sleep," he'd said. "Sleep. Get drunk.") Or maybe one of his pals had caught on. ("That Colonel Khaddourah's a strange fellow, no?")

The door opened slowly.

I clicked off the safety.

"Nick?" she whispered. I clicked on the safety.

She floated across the dark room. A chador was wrapped around her like a blanket. "Leila," I said. "Don't fool around. I'm a sick man."

She came and sat on the edge of the bed.

The chador fell open. I closed my eyes, but it was too la

te. My body had already seen her body. "Leila," I said. "You trust me too much."

"Yes. I trust you," she said, "enough."

I opened my eyes. "Enough?"

"Enough."

She ran her fingers down my face, down my neck, down my chest, where the hairs stood up and started dancing. "Define 'enough,' " I said firmly.

Now it was her turn to close her eyes. "Enough to wish… you make love to me."

My hand seemed to have a will of its own. It cupped her breast and drew out a pair of purrs from us both. "Honey," I breathed, "I'm not going to fight you very hard. Are you sure this is what you really want?"

Her neck was arched and her eyes were still closed. "I have never… been surer of anything… ever."

She moved, and the chador fell to the floor.

I suppose it's the universal dream. To be the first. Or, as they used to say on Star Trek, "to go where no man has gone before." But my God, it was sweet. That smooth, ripe, incredible body, opening slowly under my hands, going through motions that weren't just motions, but delighted, surprised first time feelings, reflexive pulsings, eager, intuitive clamping of fingers, ripplings of hip, catchings of breath. At the last moment, on the edge of the cliff, she made a kind of lyrical sound. And then she shuddered into All Grown Up.

We lay there together and I watched her face, and the little pulse that was throbbing in her throat, and I traced her body and I traced the curve of her lips with my finger until she stopped my finger with her tongue. She opened her eyes and they looked at me, shiny. She reached up and ran a hand through my hair.

And then she whispered the single word that said she was a liberated woman now.

"Again," she said.

Seventeen

There's a Yiddish expression: Drehrd offen dek. It means, Uri tells me, at the ends of the earth; in the middle of nowhere; to hell and gone. That was Rhamaz. A hundred miles south of Damascus and hundred miles from the Israeli front. The last thirty miles took us through Nowhere. A townless, treeless, lava-spattered Nothing, with hazy skies and silent dust. The landscape was dotted along the road with the rusting bodies of dead tanks and once with a crumbling stone ruin of an ancient Byzantine citadel.

Checkmate in Rio

Checkmate in Rio The Death Dealer

The Death Dealer Safari for Spies

Safari for Spies Berlin

Berlin The Death’s Head Conspiracy

The Death’s Head Conspiracy The Istanbul Decision

The Istanbul Decision The Liquidator

The Liquidator The Black Death

The Black Death The Weapon of Night

The Weapon of Night The Berlin Target

The Berlin Target Temple of Fear

Temple of Fear Earthfire North

Earthfire North Beirut Incident

Beirut Incident White Death

White Death Night of the Warheads

Night of the Warheads Double Identity

Double Identity The Spanish Connection

The Spanish Connection Rhodesia

Rhodesia Death of the Falcon

Death of the Falcon The Executioners

The Executioners Run, Spy, Run

Run, Spy, Run Circle of Scorpions

Circle of Scorpions Agent Counter-Agent

Agent Counter-Agent The Living Death

The Living Death War From The Clouds

War From The Clouds Assassin: Code Name Vulture

Assassin: Code Name Vulture The Death Strain

The Death Strain The Aztec Avenger

The Aztec Avenger Six Bloody Summer Days

Six Bloody Summer Days Operation Petrograd

Operation Petrograd Operation Che Guevara

Operation Che Guevara The Omega Terror

The Omega Terror The Terrible Ones

The Terrible Ones Assassination Brigade

Assassination Brigade Assault on England

Assault on England The Judas Spy

The Judas Spy A Korean Tiger

A Korean Tiger Operation Moon Rocket

Operation Moon Rocket Butcher of Belgrade

Butcher of Belgrade Law of the Lion

Law of the Lion Peking & The Tulip Affair

Peking & The Tulip Affair Death Island

Death Island The Jerusalem File

The Jerusalem File The Defector

The Defector The Fanatics of Al Asad

The Fanatics of Al Asad Dragon Flame

Dragon Flame Eighth Card Stud

Eighth Card Stud Operation Snake

Operation Snake The Mark of Cosa Nostra

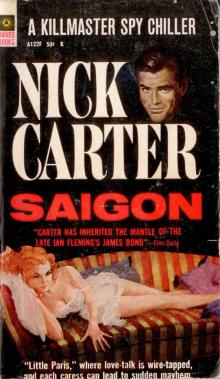

The Mark of Cosa Nostra Saigon

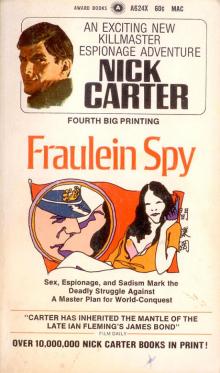

Saigon Fraulein Spy

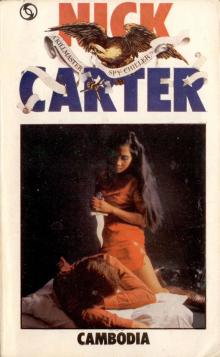

Fraulein Spy Cambodia

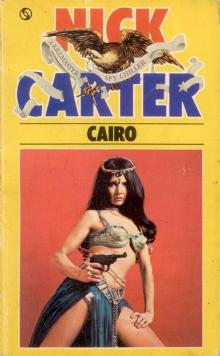

Cambodia Cairo

Cairo