- Home

- Nick Carter

Butcher of Belgrade Page 10

Butcher of Belgrade Read online

Page 10

"But, Nick, I can't arrest Richter without the police," she told me. "There is a lot of red tape involved in getting him turned over to the custody of our government. The police must be involved."

"I understand," I said. "But remember that West Germany is one of the free countries that will suffer if this device reaches the hands of KGB. As a matter of fact, I believe that Richter expects to conclude a sale of the device with a Russian right here in Belgrade. They may have done so already. At any rate, Ursula, I'm asking you to give me a crack at Richter and his radio before we call in the Yugoslavs for help in his arrest."

She thought a moment. "I want to help you capture Richter."

"Yes, you may come along," I agreed.

She smiled. "All right, Nick. I will wait before I call the police, but they may have ideas of their own, of course. I think I saw a man watching this hotel. I must assume that they can't quite trust me."

"That makes sense," I said. "You are not, after all, a good Communist."

She smiled that broad German smile, at me, and the blue eyes flashed. "I am not even a good girl," she said.

"I'd have to disagree with that."

She was wearing a robe that tied at the waist, because she had just come from the shower. She untied the robe now and let it fall open — she was nude underneath. "I suppose I had better get dressed," she said.

I looked at her curves hungrily. "I suppose."

The robe dropped to the floor. I let my eyes travel over the thrusting breasts, and small waist, and the sweep of milky hips and thighs. I remembered Eva on the train, and I knew that Eva had triggered something inside me that was now being caressed and nurtured by the sight of Ursula.

"On the other hand," she said, moving to close the distance between us, "if Richter is at that hotel now, he will probably be there just a little longer."

"Probably," I said.

She began nibbling at my ear. And I let her start undressing me.

Ursula was building a fire in me that promised to rage out of control very soon. I helped her take the rest of my clothing off, and then I took her to the big double bed across the room. We lay down together, and the next thing I knew, she was moving over on me in the male position.

Her breasts hung down over my chest in lovely pendulous arcs. She let herself down closer to me, and the tips of her breasts rubbed gently across my chest as she kissed my face and neck with her moist lips.

She moved down to my abdomen, planting kisses delicately, and the fire burned in my groin. Then she moved further down, caressing with the full warm lips, until I could stand it no longer.

"Now, liebling?" she asked.

"Now," I answered huskily.

I pushed her over on the bed and straddled her, breathless, eager. The milky thighs came up and surrounded me, and I remember feeling them lock securely behind me as we made union. The fire erupted into a volcanic holocaust. Then there were sweet smells and lovely sounds and hot flesh as we reached a climax.

When I got a look at the Sava Hotel, I realized why Richter had chosen it. It would best be described as a flea-trap in the States — an old, decrepit building that looked as if it should have been pulled down long ago in the old section of town. The sign outside the place was so weather-beaten that one could pass it without realizing it was a hotel. It looked like the kind of place where the management would look the other way for questionable guests.

The hotel had only twenty rooms, and I could see from the number of keys placed in the mail boxes behind the desk that only a half dozen were taken. I was not surprised when the sleazy Yugoslav desk clerk did not ask to see our passports, but merely took their numbers. He considered it only a formality to satisfy the police.

While the clerk came around the desk to take my one piece of luggage, I glanced at the mail boxes again and memorized those that revealed occupancy of particular rooms. Then we climbed the stairs with the clerk. When he had opened the door and had put down my luggage, I tipped him.

Just as the clerk was leaving, a door down the hall opened, and Hans Richter came out into the corridor. I shoved Ursula back from the doorway and hid from sight myself. A moment later I sneaked a look and saw Richter and two men standing in the corridor with their backs to me. They were preparing to leave another man, whose room they had just left. The other man was Ivan Lubyanka.

Apparently Richter had sent Lubyanka to this place when he had left the Orient Express at Pivka. Now, even though Richter appeared to have found a different hiding place because of the incident at the station, he had come here with these men, who were obviously Topcon agents, to discuss the sale of the monitor device with the Russian.

Richter was not carrying the radio. Maybe he did not trust the KGB. He and his cohorts walked down the corridor to the stairway as Lubyanka closed his door.

I turned to Ursula. "It's Richter and his friends," I said. "Follow them and see where they go. Try not to get yourself killed. In the meantime, I'm going to pay a visit to a Russian friend of mine down the hall. I'll meet you at the Majestic at three. Wait an hour after that, and if I don't show, you're on your own."

She looked into my face for a brief, tender moment. "All right, Nick."

I smiled. "See you later."

"Yes."

Ursula disappeared down the corridor after Richter and his men.

A few minutes later, I knocked on the door of Lubyanka's room. After a short pause, Lubyanka's voice came from the other side of the door. "Yes?"

I was pretty good at dialects and voices, especially after I had had a chance to hear them, so I cleared my throat and tried my best to sound like Hans Richter.

"Blücher," I said.

The lock on the door clicked as I pulled out the Luger. When the door opened and I saw Lubyanka's surprised face, I did not wait for an invitation to enter the room. I kicked at the door savagely and smashed it into the room. It hit Lubyanka in the chest and head and knocked him to the floor.

Lubyanka started for his gun on a distant table, but I stopped him. "Hold it right there."

He turned and saw the Luger aimed at his head. Then glanced at the distance between him and the Webley and decided it was a lousy risk.

"It is you again," he said bitterly.

"I'm afraid so, old man. All right, on your feet. And keep away from your plaything on the table."

Lubyanka rose slowly, blood dripping from his cheek and mouth. His lip was already swelling. I moved to the door and closed it, keeping an eye on the KGB man every moment. His eyes held a great dislike for me.

"Now," I said, "you and I are going to have a nice talk."

"We have nothing to talk about," he answered grimly.

"I think we do."

He grunted and moved his hand to the cut on his cheek. "You have come to the wrong man, I'm afraid."

"Maybe," I said. "But if I have, it will be too bad for you." I watched his face as the impact of that statement sunk in.

"We haven't made a deal yet," he told me. "Consequently, I do not have what you are looking for."

"If Richter still has it, where does he keep it?" I asked.

"Richter?"

"Excuse the lapse. He's Horst Blücher, to you."

Lubyanka thought about that a moment. "I do not have any idea where the device is. He is very secretive and evasive."

"Maybe he doesn't trust you, Lubyanka," I said, needling him a little.

He gave me a look. "I do not trust him."

The corner of my mouth moved. It always gave me a little pleasure to see two unpleasant people trying to outsmart each other. "Well, there is one thing for sure, Lubyanka. You know where to contact him. And I want you to tell me that."

Lubyanka had moved over to an unmade bed. I watched him closely and kept the Luger trained on him. "He has not told me where he is staying," he said slowly.

"You're lying, Lubyanka. And that will get you a 9mm slug in the head." I moved closer to him. "I want the truth, and I want it now. Where can I find Rich

ter?"

Lubyanka's eyes suddenly looked flat, desperate. Surprising me, he grabbed a big pillow from the bed and turned toward me with it in front of him. I had no idea what he was doing, so I took no chances. I fired, and the Luger exploded in the small room.

The slug was buried in the thick pillow and never reached to Lubyanka's chest. In the meantime, Lubyanka hurled himself at me, still holding the pillow between us. I raised the level of my aim and fired again at his head, but my shot narrowly missed as he fell on me.

Lubyanka hit at my gun arm and knocked it high, but I still held the gun. Now the pillow was gone, and Lubyanka was twisting violently at my arm with both hands. We hit against a wall, and I lost the gun.

Then we both slid to the floor, struggling for dominance. I threw a fist into Lubyanka's already bloody face, and he managed to return the blow before breaking away from me. Then he was reaching for the Webley that was now near him on the table.

He grabbed the gun before I could reach him, but he could not get at the trigger assembly in time to fire it. When I reached him, he hit out savagely with the gun, striking me across the side of the head with the heavy barrel.

I fell back near a window, against the wall. Lubyanka then got to his feet and pointed the Webley at me again, but I found the strength to grab at his gun hand and pull him before he could fire. He sailed past me and crashed through the window. The glass shattered loudly and rained down around me as I turned and watched Lubyanka's body hurtle into the open air outside — his arms were spread wide, as he grasped for something to save him.

There was a short silence as Lubyanka fell, then I heard a scream. I leaned out through the broken glass and saw that he had hit a second floor balcony. He was impaled on the pickets of an iron balustrade, facing up with his eyes still open, and two of the pickets protruded through his chest and abdomen.

I swore at myself. Lubyanka would tell me nothing now. Retrieving Wilhelmina, I quickly left the small room and hurried down the corridor just as the sound of footsteps came from the front stairs. I avoided them by using the rear service stairs to reach the street.

Eleven

"This is the place. This is where Richter went with the two men," Ursula told me.

We were huddled in a dark doorway on a narrow street, staring through the night at an old building across the way. Ursula was becoming very anxious, but she tried not to show it.

"Do you think they might have seen you following them?" I asked.

"I don't think so," she said.

The building across the street was an apartment house. Ursula had told me that they had entered the street room on the second floor, but there were no lights on at the moment.

"Well, let's go up there and take a look," I suggested.

"All right, Nick." She reached into her purse for the Webley.

"I want you to keep me well covered up there," I said. "This could be a trap."

"You can count on me, Nick."

When we got up to the room where we supposed Richter and his men had been, it appeared to be vacant I entered carefully, Wilhelmina out, but no one was there.

"Come on in," I told Ursula.

She joined me, closed the door, and glanced around the place. It was a large room with a private bath. Paint was flaking off the walls, and the plumbing looked antique. There was a lumpy cot in a corner, a scarred wooden table, and several straight chairs to one side.

"Some place," I commented. I slipped the Luger back into its holster. I walked over to the cot. It seemed that somebody had recently lain on it.

"There is no luggage or anything here," Ursula noted. "We may have lost him already."

"Let's take a look around," I said.

We tore the place apart. There was evidence that Richter had been there — a butt of one of his favorite cigarettes; a bottle of wine, almost empty; and in a wastebasket, his discarded train ticket I could find nothing that indicated he would be returning to this room. In fact, all the evidence indicated that he had left it for good.

"Now what do we do?" Ursula asked.

"I don't know," I told her. I wandered back into the bathroom and glanced slowly around. It seemed to me that there was some place in the room that we had overlooked. I looked into the empty medicine chest again.

Then I turned to the toilet. The top was down on it. I lifted the lid and looked into the bowl.

There I saw the piece of wet crumpled paper floating in the clear water.

I fished it out and took a look at it. It was only a fragment of paper from a larger piece that had evidently been torn up and flushed to oblivion, but there were several handwritten letters on it.

"I've got something," I said.

Ursula came and looked over my shoulder. "What is it?"

"It looks as if Richter tried to get rid of this down the toilet. Can you make out what the letters are?"

She took a look at it. "This is Richter's handwriting," she said. She made a face as she turned the note slightly. It looks like it is written in Serbo-Croatian, Nick. Perhaps the beginning of the word national. And another letter, the start of another word."

I squinted at it "National. But what's the second word?"

"M — U — S — museum, The National Museum."

I looked quickly at her. "The museum. Does It have a checkroom?"

"I suppose so," she said.

"Richter would have no reason to use the museum for a rendezvous," I said. "We know he has already met Lubyanka at the Sava Hotel, and possibly here."

"That is true," Ursula said, but not following me.

"Well, let's say you wanted to deposit that radio somewhere for safekeeping for a couple of days. You can't use a baggage checkroom at the Central Station or the airport because the police are watching for you there. But why not use the checkroom at a public place like the museum?"

"But articles are checked there only for the time the visitor is in the museum," Ursula reminded me.

I thought about that a moment. "They would keep an article for a couple of days, though, expecting its owner to return. But let's say Richter did not want to depend on that possibility. Maybe he checked the radio at the museum and then called them later in the day to say that he had neglected to pick it up when he left. He would have promised to get the radio within twenty-four or forty-eight hours. He would be assured then that they would take special care to hold it for him."

"That is a good theory, Nick. It is worth checking out."

"We'll be at the museum first thing in the morning," I said. "If Richter finds out about Lubyanka tonight, he will probably decide to leave Belgrade immediately, but not without that radio. If he did stash it at the museum, we would want to beat him there. It may be our last chance for contact with him."

"In the meantime," she said, "you need some rest. And I have an especially comfortable room at the Majestic."

"That's a nice offer," I said.

* * *

We were at the National Museum when it opened the following morning. It was a sunny spring day in Belgrade. There were bright green buds on the tall trees in Kalamegdan Park. The hydrofoil tour boats plied the placid waters of the Danube, and the bustling traffic seemed somehow less hectic. But the museum itself sat monolithic and gray in the bright morning; it was a vivid reminder that Ursula and I were not there for diversion.

The interior was all high ceilings and sterile glass cases, a striking contrast with the sunny morning on the other side of its thick walls. It didn't take us long to find the checkroom. The Yugoslav on duty there was still waking up.

"Good morning," I greeted him. "A friend of ours left a portable radio here and forgot to take it away with him. He has sent us to pick it up." I was speaking in my best German accent.

He scratched his head. "Radio? What is this?"

I decided to try speaking to him in Serbo-Croatian. "A radio. One that is carried on a strap."

"Ah," he said. He moved to a corner of the small room while I held my breath and reached tow

ard a shelf. He pulled down Richter's radio. "I have one left here by a fellow named Blücher, a Swiss."

"Yes," I said, glancing at Ursula. "That's it. Horst Blücher is the full name."

He looked on a slip. "Yes. Do you have some identification, Mr. Blücher? I don't seem to remember your face."

I controlled my impatience. I had already decided to take the radio by force if it was necessary. "I am not Horst Blücher," I said deliberately. "We are his friends who have come to claim the radio for him."

"Ah. Well, Mr. Blücher should have come himself, you see. That is the rule."

"Yes, of course," I said. "But Mr. Blücher has fallen ill and is unable to come for the radio. We hope you'll understand. You will be doing him a great favor if you give us the radio to take to him."

He looked at me suspiciously and then at Ursula. "Did he give you the claim slip?"

Now Ursula put on an act. "Oh, dear! He mentioned that we should take the slip just before we left. But he forgot to give it to us. He is quite ill." Then she turned on the charm. "I hope you will not be technical about the slip. Mr. Blücher so wanted to hear some beautiful Yugoslav music while he is here."

"Ah," the man said, looking into her cool blue eyes. "Well, I can understand that. Here, you may take the radio. I have no facilities for storing it here anyway."

"Thank you very much," I told him.

He ignored me and handed the radio to Ursula. "Tell your friend to get well soon so that he may enjoy his stay in Belgrade."

"Thank you," Ursula said.

She took the radio, and we left the checkroom. But on our way out of the building, I found that my victory was short-lived. Two men stepped out of an alcove in a corridor, and no one else was around. They both held guns. They were the two Topcon men we had seen earlier with Richter, the men Ursula had followed.

"Stop there, please," the taller one ordered.

I groaned inaudibly. Another few minutes and the monitor device would have been mine. Damn these men! This was the second time I had been in possession of it, only to have it snatched away from me. Ursula was not quite as upset as I was. She had lost all contact with Richter, despite the recovery of the radio, and now these men had reestablished that contact I found myself wondering if she would live to benefit from this turn of events.

Checkmate in Rio

Checkmate in Rio The Death Dealer

The Death Dealer Safari for Spies

Safari for Spies Berlin

Berlin The Death’s Head Conspiracy

The Death’s Head Conspiracy The Istanbul Decision

The Istanbul Decision The Liquidator

The Liquidator The Black Death

The Black Death The Weapon of Night

The Weapon of Night The Berlin Target

The Berlin Target Temple of Fear

Temple of Fear Earthfire North

Earthfire North Beirut Incident

Beirut Incident White Death

White Death Night of the Warheads

Night of the Warheads Double Identity

Double Identity The Spanish Connection

The Spanish Connection Rhodesia

Rhodesia Death of the Falcon

Death of the Falcon The Executioners

The Executioners Run, Spy, Run

Run, Spy, Run Circle of Scorpions

Circle of Scorpions Agent Counter-Agent

Agent Counter-Agent The Living Death

The Living Death War From The Clouds

War From The Clouds Assassin: Code Name Vulture

Assassin: Code Name Vulture The Death Strain

The Death Strain The Aztec Avenger

The Aztec Avenger Six Bloody Summer Days

Six Bloody Summer Days Operation Petrograd

Operation Petrograd Operation Che Guevara

Operation Che Guevara The Omega Terror

The Omega Terror The Terrible Ones

The Terrible Ones Assassination Brigade

Assassination Brigade Assault on England

Assault on England The Judas Spy

The Judas Spy A Korean Tiger

A Korean Tiger Operation Moon Rocket

Operation Moon Rocket Butcher of Belgrade

Butcher of Belgrade Law of the Lion

Law of the Lion Peking & The Tulip Affair

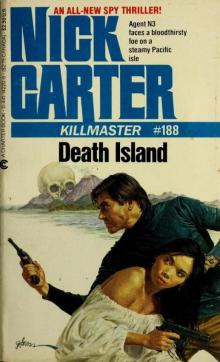

Peking & The Tulip Affair Death Island

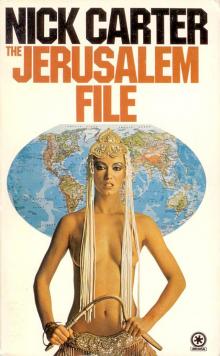

Death Island The Jerusalem File

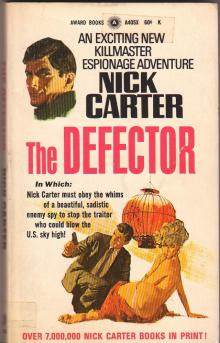

The Jerusalem File The Defector

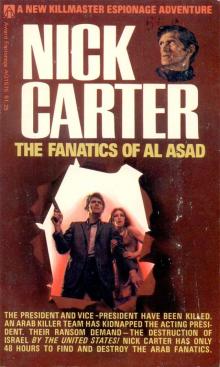

The Defector The Fanatics of Al Asad

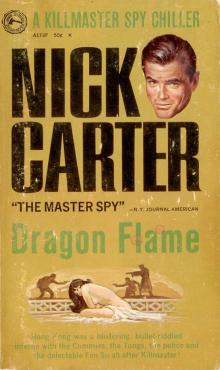

The Fanatics of Al Asad Dragon Flame

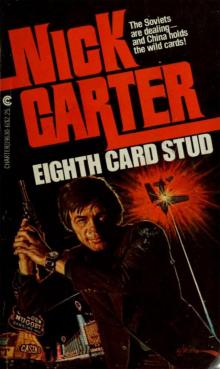

Dragon Flame Eighth Card Stud

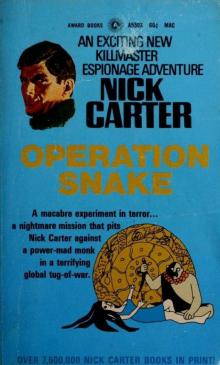

Eighth Card Stud Operation Snake

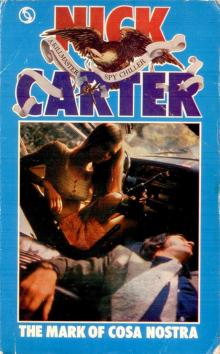

Operation Snake The Mark of Cosa Nostra

The Mark of Cosa Nostra Saigon

Saigon Fraulein Spy

Fraulein Spy Cambodia

Cambodia Cairo

Cairo