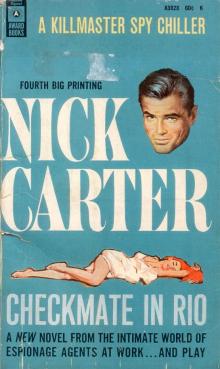

Checkmate in Rio

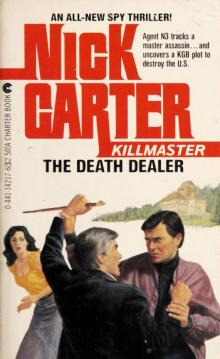

Checkmate in Rio The Death Dealer

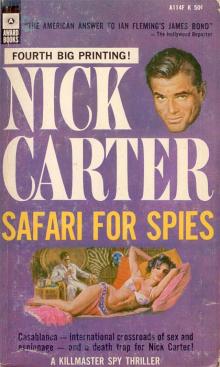

The Death Dealer Safari for Spies

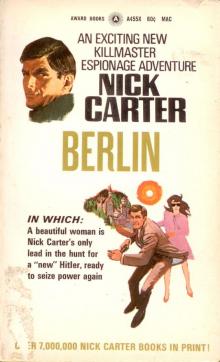

Safari for Spies Berlin

Berlin The Death’s Head Conspiracy

The Death’s Head Conspiracy The Istanbul Decision

The Istanbul Decision The Liquidator

The Liquidator The Black Death

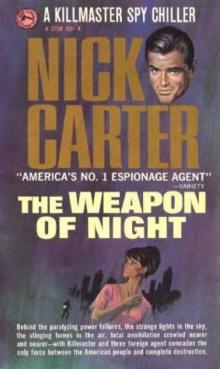

The Black Death The Weapon of Night

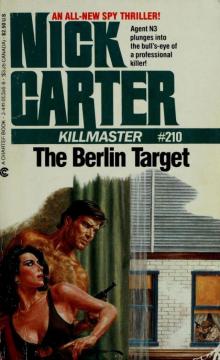

The Weapon of Night The Berlin Target

The Berlin Target Temple of Fear

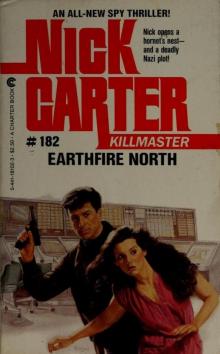

Temple of Fear Earthfire North

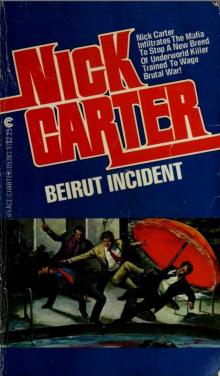

Earthfire North Beirut Incident

Beirut Incident White Death

White Death Night of the Warheads

Night of the Warheads Double Identity

Double Identity The Spanish Connection

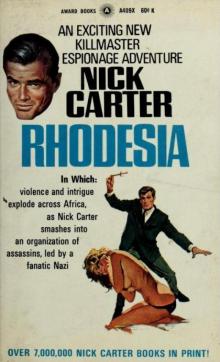

The Spanish Connection Rhodesia

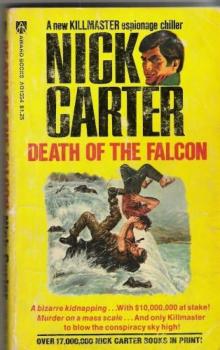

Rhodesia Death of the Falcon

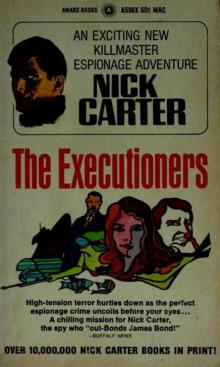

Death of the Falcon The Executioners

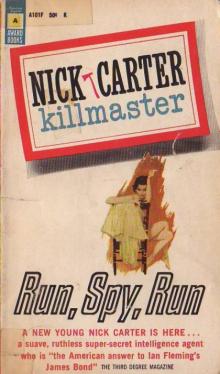

The Executioners Run, Spy, Run

Run, Spy, Run Circle of Scorpions

Circle of Scorpions Agent Counter-Agent

Agent Counter-Agent The Living Death

The Living Death War From The Clouds

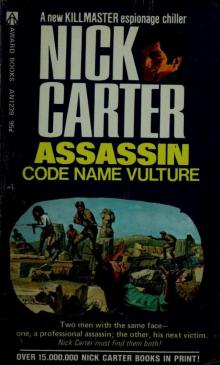

War From The Clouds Assassin: Code Name Vulture

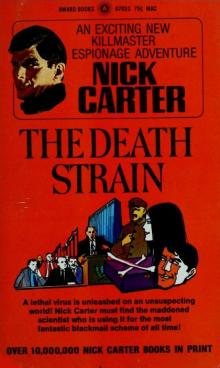

Assassin: Code Name Vulture The Death Strain

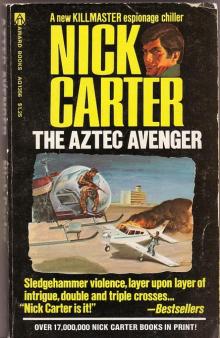

The Death Strain The Aztec Avenger

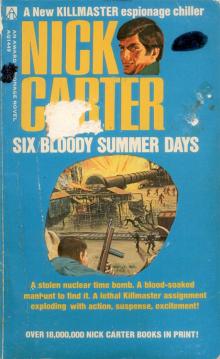

The Aztec Avenger Six Bloody Summer Days

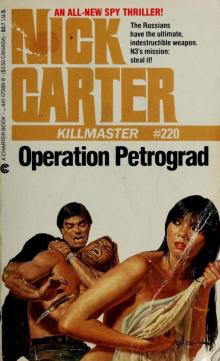

Six Bloody Summer Days Operation Petrograd

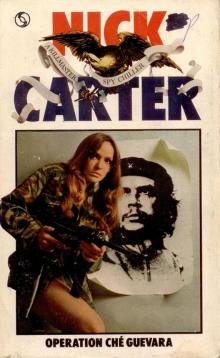

Operation Petrograd Operation Che Guevara

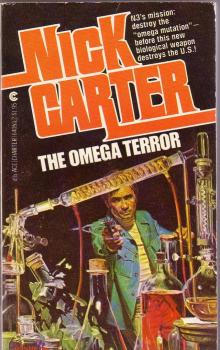

Operation Che Guevara The Omega Terror

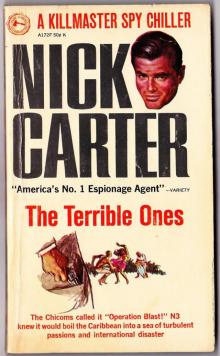

The Omega Terror The Terrible Ones

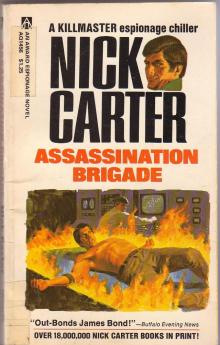

The Terrible Ones Assassination Brigade

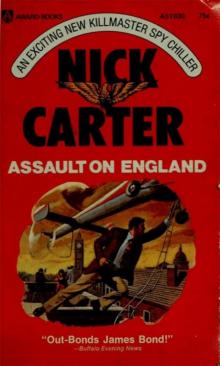

Assassination Brigade Assault on England

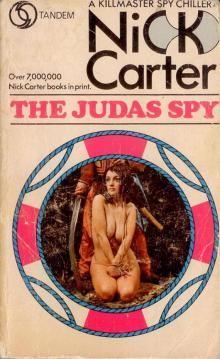

Assault on England The Judas Spy

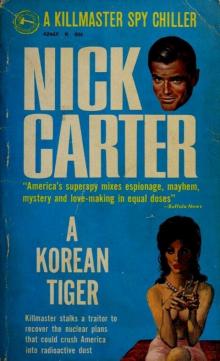

The Judas Spy A Korean Tiger

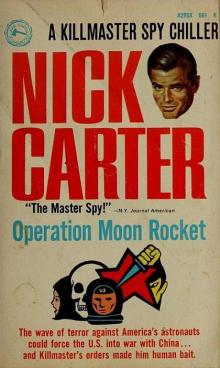

A Korean Tiger Operation Moon Rocket

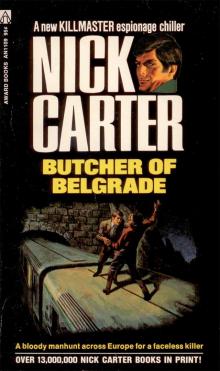

Operation Moon Rocket Butcher of Belgrade

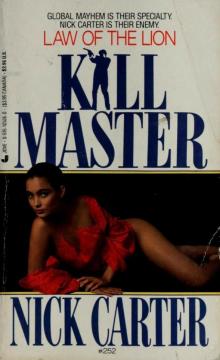

Butcher of Belgrade Law of the Lion

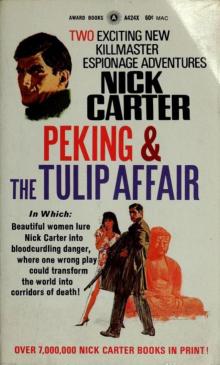

Law of the Lion Peking & The Tulip Affair

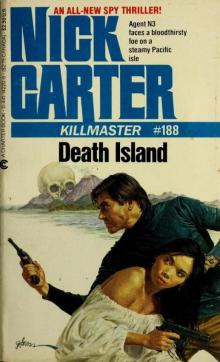

Peking & The Tulip Affair Death Island

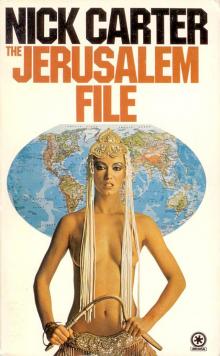

Death Island The Jerusalem File

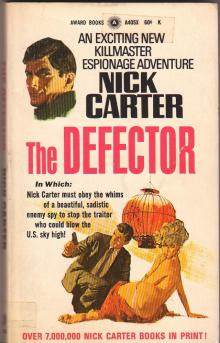

The Jerusalem File The Defector

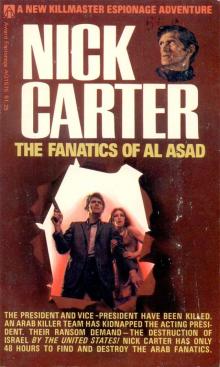

The Defector The Fanatics of Al Asad

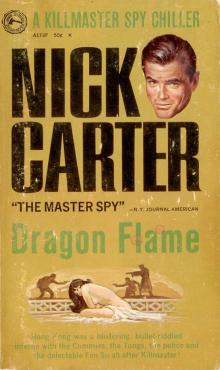

The Fanatics of Al Asad Dragon Flame

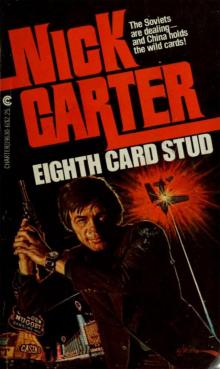

Dragon Flame Eighth Card Stud

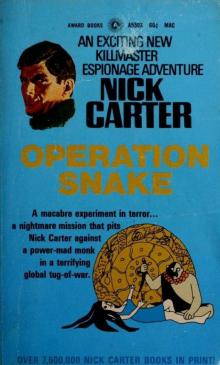

Eighth Card Stud Operation Snake

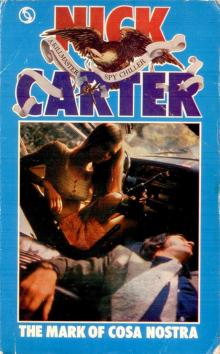

Operation Snake The Mark of Cosa Nostra

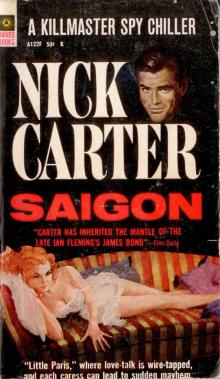

The Mark of Cosa Nostra Saigon

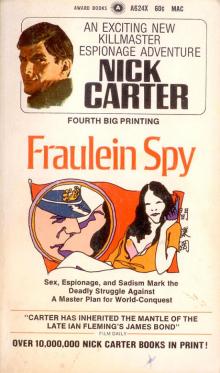

Saigon Fraulein Spy

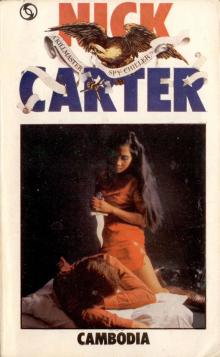

Fraulein Spy Cambodia

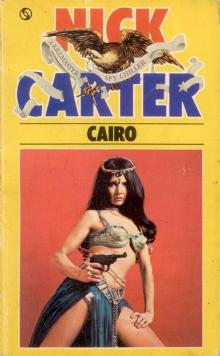

Cambodia Cairo

Cairo